Pentest Chronicles

Vishing – How It Works and Why It’s So Effective: Insights from Commercial Social Engineering Tests

Jacek Siwek

February 14, 2025

Why Does Vishing Work? Vishing exploits psychological factors and behavioral patterns that influence human decision-making:

• Trust in authority – If the caller claims to be from IT or a bank, people generally assume they are legitimate.

• Time pressure – Attackers often stress the urgency of the issue (e.g., a potential major system failure), which makes the victim react quickly rather than think critically.

• Natural willingness to help – Most people don’t want to "cause problems" and try to be as cooperative as possible.

Even individuals who are aware of cyber threats can fall victim under the right psychological pressure, sharing information they would normally keep confidential.

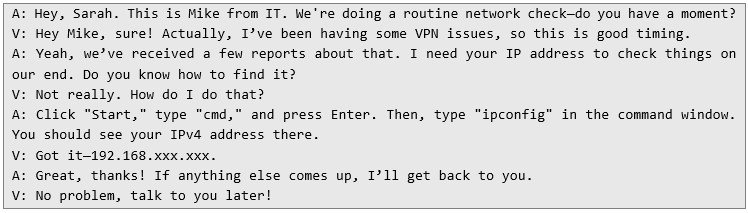

Examples of Vishing Scenarios1. Simple Attack – Extracting Information Through Conversation The easiest and most common vishing technique involves gathering useful information without requiring the victim to install anything. The attacker simply calls, pretending to be a colleague.

Example ConversationA – AttackerV – Victim

This seemingly innocent exchange provides the attacker with valuable information, potentially allowing further network reconnaissance.

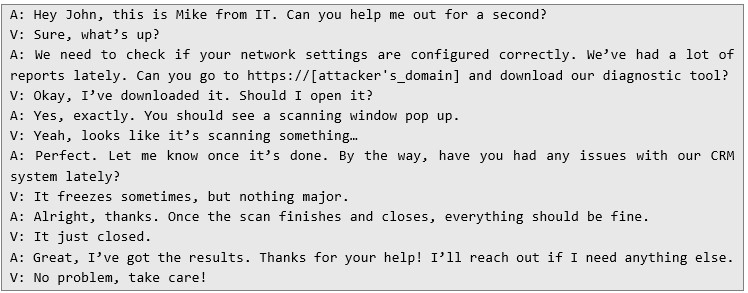

2. Intermediate Attack – Convincing the Victim to Download Malware In this version, scammers still rely on trust and credibility but take it a step further by convincing the victim to download and run a "diagnostic" application, which is actually malware.

Example Conversation

The victim unknowingly runs a malicious file that could grant the attacker access to their computer.

The victim unknowingly runs a malicious file that could grant the attacker access to their computer. 3. Advanced Attack – Overcoming the Victim’s Doubts In this case, the victim initially suspects something is off. However, the attacker uses social engineering techniques (referencing internal procedures, stressing urgency, and implying consequences) to break through their hesitation.

Example Conversation

Despite her initial hesitation, the victim is persuaded to take a risky action.

Despite her initial hesitation, the victim is persuaded to take a risky action. How Do Attackers Prepare? Before making a call, scammers often gather information about the company's structure, technologies used, and employee names. This allows them to reference specific departments, tools, or internal processes, making them seem more legitimate.

In social engineering tests conducted by various pentesting teams (including ours), we’ve seen that most employees can be convinced to install unknown applications or share confidential information, simply because they believe they are speaking to IT staff.

To increase their chances of success, attackers leverage various social engineering techniques, including:

1. Pretexting – Building a Believable Story Attackers create a convincing scenario (pretext) to justify their requests. This could involve posing as:

• An IT technician conducting routine security checks.

• A bank employee verifying suspicious transactions.

• A senior manager needing urgent access to an account.

The key to pretexting is using industry-specific jargon and internal terminology to appear credible. Attackers may reference real employee names, software systems, or past incidents to make their story more believable.

2. OSINT (Open-Source Intelligence) Gathering – Researching the Target Scammers use publicly available information (e.g., LinkedIn, company websites, social media) to learn about:

• Employee roles and reporting structures.

• Company technology stack (software, security tools, vendors).

• Internal terminology and recent announcements.

This information helps attackers tailor their approach, making their requests seem more authentic.

3. Urgency and Fear Tactics – Creating a Sense of Panic Attackers often fabricate emergencies to rush their victims into compliance, such as:

• Claiming there is an ongoing cyberattack that requires immediate action.

• Warning that a failure to respond could lead to job termination or financial loss.

• Stating that critical services will be disabled unless the victim cooperates.

Under pressure, people tend to react instinctively rather than rationally, increasing the likelihood of compliance.

4. Reciprocity and Flattery – Gaining Trust Through Small Favors Attackers sometimes start with small, harmless requests to build rapport before asking for sensitive information. Examples include:

• Asking an employee to confirm minor details ("Can you verify if this is your correct extension number?").

• Complimenting the victim’s knowledge or expertise to make them feel valued ("You seem really knowledgeable about our CRM system—can you help me reset my access?").

5. Exploiting Familiarity and Internal Connections Attackers drop the names of real employees or departments to sound more credible:

• “I got your number from Tom in Finance—he said you’re the best person to help.”

• “I just spoke with your manager, Lisa, and she approved this installation.”

HOW TO DEFEND AGAINST VISHING:

1. Employee Training Regular security awareness training and simulated phishing calls help employees recognize manipulative tactics and respond appropriately.

2. Limited Trust Policy If someone calls claiming to be from IT but is unfamiliar, verify their identity (e.g., call the official IT department number yourself).

3. Verification Procedures Establish clear rules within the company, such as:

• Never share passwords or credentials over the phone.

• Never install software without direct confirmation from a manager.

4. Staying Vigilant IT departments should not ask employees to perform suspicious actions, such as installing unknown software from an unofficial website.

Next Pentest Chronicles

When Usernames Become Passwords: A Real-World Case Study of Weak Password Practices

Michał WNękowicz

9 June 2023

In today's world, ensuring the security of our accounts is more crucial than ever. Just as keys protect the doors to our homes, passwords serve as the first line of defense for our data and assets. It's easy to assume that technical individuals, such as developers and IT professionals, always use strong, unique passwords to keep ...

SOCMINT – or rather OSINT of social media

Tomasz Turba

October 15 2022

SOCMINT is the process of gathering and analyzing the information collected from various social networks, channels and communication groups in order to track down an object, gather as much partial data as possible, and potentially to understand its operation. All this in order to analyze the collected information and to achieve that goal by making …

PyScript – or rather Python in your browser + what can be done with it?

michał bentkowski

10 september 2022

PyScript – or rather Python in your browser + what can be done with it? A few days ago, the Anaconda project announced the PyScript framework, which allows Python code to be executed directly in the browser. Additionally, it also covers its integration with HTML and JS code. An execution of the Python code in …